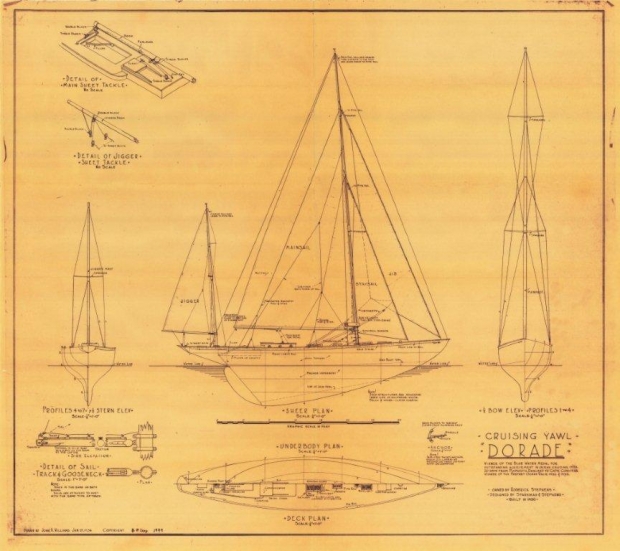

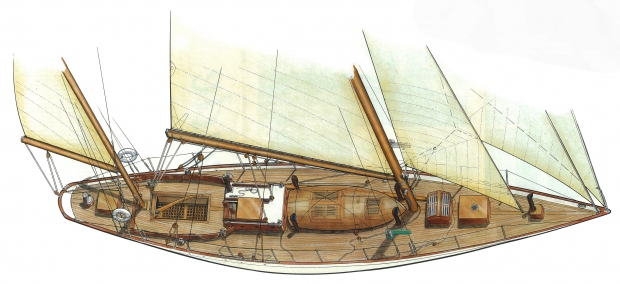

Dorade became the most famous ocean racing yacht in the world. As the first major blue water design to be built to the drawings of her 21-year-old designer, Dorade’s keel was laid just weeks after the Stock Market Crash of 1929, and her launching in the spring of 1930 coincided with the slide of the nation into the Great Depression. Despite such inauspicious timing, this yacht, her young designer and youthful, attractive crew became a sensation on both sides of the Atlantic and on both coasts of America. Dorade introduced and validated the early yacht design concepts of Olin Stephens and influenced, in one way or another, nearly all developments in yacht design for the next three decades. Her rigging and deck fixtures, developed in large part by Olin’s younger brother, Roderick Stephens Jr., still make the name Dorade commonplace today. Her combination of speed, sea-keeping ability, stunning beauty and small size, coupled with her startling racing success, kept the eye of the public on her and on those aboard her. It is difficult to find a serious book about yacht racing in the 20th century that does not refer to her and to her impact on the popularity of ocean racing and the development of yacht design. Dorade was and is a breakthrough yacht, a unique point in the continuum of yacht architecture that defines a change in thinking about how an ocean racing yacht should be shaped and rigged and a present-day reminder of that inflection point. This is her story, from her genesis to her enduring fame, from her influence on design development to her long racing success. Most importantly, it is a record of her owners, triumphs, travels, travails and resurrections, and it is a biography of a singular, defining American yacht, continuously adored and still racing.

Forward

by Llewellyn Howland III

The story is as old as that of the great artificer Daedalus and his impetuous and headstrong son, Icarus. To refresh your memory: Daedalus and Icarus find themselves consigned by King Minos to the Labyrinth, a fantastic maze of a prison from which there is no possible exit by land or sea. Undaunted, Daedalus fashions from feathers and wax a dandy pair of artificial wings for himself, another fine pair for his son. The wings not only fit well and look well, they work well, and Daedalus and Icarus take off from the Labyrinth, becoming the first mortals ever to fly through the air.

But there is one problem. Disregarding his father’s firmly stated and very practical instructions, Icarus, having followed his father into the air and away from the Labyrinth, decides to take a quick joy ride up to the sun. All too soon, the wax begins to melt and the wing feathers to flutter away. Icarus stalls. Loses altitude. Crashes and burns.

Generations of schoolchildren have learned the moral of this tale: Father knows best; stay away from the sun; and, if you must fly at all, be sure to wear your seat belt. Translated into terms even sailors can understand, the story of Icarus teaches us that the prudent way is the best way. The maritime lesson to take away from the fall of Icarus is that the more orthodox in form an ocean racing yacht may be, the more conservative in design and rig, the better the likelihood that it will safely lead the fleet home.

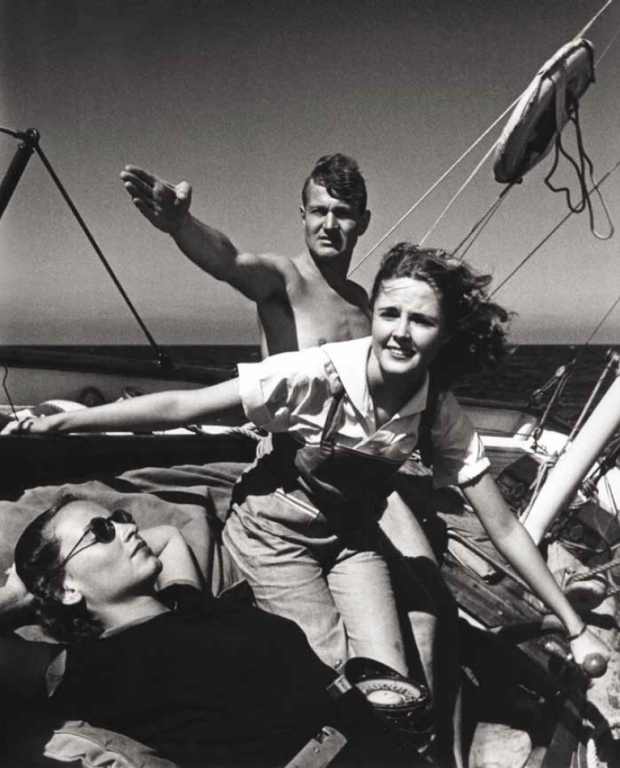

Douglas Adkins’ superb biography of the ocean racing yawl Dorade reads like a modern-day retelling of the Icarus legend. But it is a retelling with dramatic differences. For one thing, Adkins’ account is as factual and as truthful as careful and extensive research can make it. For a second, it is not about an impetuous kid flying too close to the sun. Rather, it begins with two wonderfully able and self-assured young brothers—Olin and Rod Stephens Jr.—who not only fly, in a yachting context, as close to the sun as man has ever flown, but circle it repeatedly, successfully, and in seeming defiance of the laws of gravity.

It is a story in which the father, Roderick Stephens Sr., an early-retired New York coal merchant with limited sailing skill and experience—has a deep and abiding faith in his sons’ talent and character and good sense and lets them take wing. Believing in the boys, the elder Stephens risks reputation, treasure and even physical well-being to support the construction of a boat to a largely unproven design by vi son Olin, scarcely out of his teens, for international competition against some of the finest offshore racing yachts of the day.

Most important of all, it is the story of a narrow, 52-foot yawl launched in May 1930, at the start of the Great Depression. Named after the blunt-nosed warmwater dolphinfish, Dorade has many characteristics of an International Rule metre boat. Her accommodations are Spartan. She is quite lightly and quickly built on a tight budget. She has no engine. She sails on her ear. She is a great roller in a seaway. Her berths are likened to coffins. Who in their right minds would want to own or go racing offshore in such a boat as this?

Dorade performed well in her shakedown summer, taking second in Class B and the All Amateur Prize in the 1930 Bermuda Race and silver in various club races. In this respect, she was a success from the very first. But it was her extraordinary victory under the command of Olin Stephens in the 1931 Transatlantic Race from Newport, Rhode Island, to Plymouth, England, that put her on the path to yachting immortality. Competing against the best that rival designers had to offer, she made the North Atlantic passage in 16 days and 55 minutes. The next boat to finish—a much larger boat at that—crossed the line two days later. When the final results were tallied, Dorade was the winner by over four days on corrected time. Winning, she brought about a revolution in the design of ocean-racing yachts.

Olin Stephens, a truly modest man with nothing to be modest about, always ascribed Dorade’s victory in the 1931 Transatlantic Race to luck. No question Dorade was a lucky ship in that race, as she has proved to be in countless subsequent races and adventures over a career that now spans 80 years. However, as each new ocean racer, International Rule sloop, cruising class auxiliary, one-design daysailer, motor sailer, and America’s Cup defender issued forth from the Sparkman & Stephens drafting room over the next many decades, wise sailors quickly learned to discount the fabled Stephens luck. Boats designed by Olin Stephens and tuned by his brother Rod earned their victories on merit, not chance. The characteristics that made Dorade a great and revolutionary boat in 1930-’31 have made her great and revolutionary ever since.

Douglas Adkins has written a long-awaited history of Dorade. But she herself is just one player in his narrative, and the Stephens brothers and their father were only the first of a long and colorful line who have owned, helped build or restore, cut sails for, sanded the bottom of, raced on or against, sailed or cruised on or in company with, and, in at least one instance, died for her.

As this book makes clear, the relationship between yachts and those who design, build, own, and sail them is dynamic and complex. Not every serious sailor, not even young sportsmen as wealthy and well-connected as Dorade’s early West Coast owners, would welcome the celebrity—sometimes even notoriety—that Dorade has tended to confer those who have owned her. Conversely, not every owner of Dorade has won the silver he dreamed of or the recognition and acceptance he sought as the owner of such a fast and famous boat. To hold the tiller of Dorade as vii she takes the cannon at the finish line may be the fulfillment of a lifelong dream. To be involved in a spectacular collision and sinking on the race course, or even to suffer a succession of minor, but highly visible, lapses of seamanship or good judgment, can rapidly turn the joys of possession into psychic burdens too great to bear.

Variously owned on Long Island Sound, in San Francisco and Seattle, on Orcas Island, in the Mediterranean at Argentario in Italy and Antibes on the Cote d’Azure, and latterly in Newport, Rhode Island, Dorade has outlived her famously long-lived designer and many of her former owners. She has crossed the Atlantic often and visited Hawaii at least twice. She has endured countless repairs and undergone restorations both minor and massive. Love affairs have begun and marriages have ended aboard her. She has been a dry ship (under the Stephens ownership) and, at times, a very wet one. Races she has won (and lost) are now almost past counting.

What a life she has led! And with what grace and dignity and firmness of purpose she has sought to do the will of her many masters! This is not to say that Dorade is unique in these respects. Other sailing yachts, and not just those designed by Sparkman & Stephens, have lived as long or longer and have given as much pleasure (some even with a lot less rolling in a seaway and with berths far more comfortable than coffins). Their owners have been no less varied in temperament, background, and ambition, no less obsessed by the sea in all its moods and ways.

But these other yachts were not in signaling distance of the English lighthouse known as The Lizard at 5:45 on the morning of Tuesday, 21 July, 1931, when a narrow yawl named Dorade ghosted by on her way to Plymouth. In response to Dorade’s request for her place in the order of finish in the Transatlantic Race, the station keeper hoisted the flags N A X: “You are first.” As Doug Adkins demonstrates so convincingly, so entertainingly, and so eloquently, Dorade has been first ever since.